Paideia: The Soul of Classical Christian Education (Pt. 3)

Chapter One: Untitled Primer on Classical Christian Education

I’m currently revising the second draft of a short seven-chapter primer on Classical Christian Education and would like to invite you into the process by sharing this “work in progress” publicly. Please feel free to share your feedback; and, please help me title the book.

Introduction

Chapter One (Pt. 1)

Chapter One (Pt. 2)

I had intended to drop each chapter, serially, but the second draft of Chapter One comes in at roughly 3,500 words—a bit longer than reasonable for Substack. So, I’m dropping Chapter One in three post over the next three days. Below is the second installment.

CHAPTER ONE (Pt. 3)

Paideia: The Soul of Classical Christian Education

1.6 The Harmony of Knowledge and Virtue

One of the most dangerous lies of modern education is that knowledge and virtue can be separated—that one can be intellectually brilliant and morally bankrupt, and still be considered “educated.” The classical tradition rejects this bifurcation. In reality, it is a modern innovation, and an artificial innovation at that.1 Plato, for example, asserts that to try to educate a vicious person would be like trying to insert vision into blind eyes. The only way to actually enlighten him would be to turn his body around so his eyes were toward the sun (i.e., transformation).2

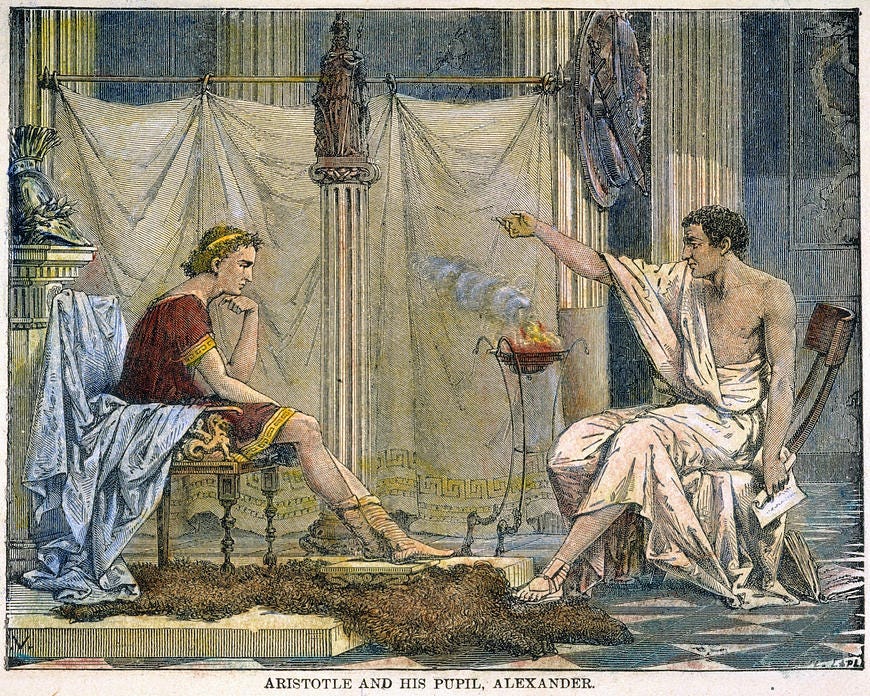

Aristotle similarly says such an attempt would be akin to throwing a rock in the air ten thousand times believing you could habituate it to always move upward instead of fall to the ground when you let go if it.3 Such attempts are more than futile; they’re nonsensical because the pursuit of knowledge is ultimately a means for virtue. St. Augustine reiterates this when he contends that knowledge and learning are meant to rightly order our loves, ordo amoris.4 Dante’s Divine Comedy was meant to poetically illustrate how a proper pursuit of knowledge has a transcendent effect, leading the learner to a more comprehensive understanding of the cosmos and ultimately a better understanding of God, the Beatific Vision.5

Another way to understand the essential relationship between knowledge and virtue is to consider C. S. Lewis’s famous Chest-Magnanimity-Sentiment statement. Drawing from the Platonic conception of the human soul, he explained that the intellect (noētikós) was powerless on its own to manage or control the human appetites or sensual emotions (epithumeō). The intellect needs a strong man to aid him, the spirit (thumós). Lewis says,

without the aid of training emotions (i.e., virtue) the intellect is powerless against the animal organism…Reason in man must rule the mere appetites by means of the ‘spirited’ element. The head rules the belly through the chest—the seat of emotions organized by trained habits into stable sentiments…these are the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral man (intellect) and visceral man (emotions). It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.6

To try and separate knowledge from virtue, says Lewis,

is to produce men without chests…In sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the gelding be fruitful.7

Knowledge without virtue is dangerous; virtue without knowledge is fragile. True education is the harmonious cultivation of both as inseparable facets of man qua man. Paideia unites the training of the mind and the formation of the heart (the seat of the emotions) so that students are equipped to live virtuously—justly.

1.7 Teachers as Shepherds of Souls

Modern educators are therapeutically oriented, “inquiring into the nature of the immature mind and mastering the techniques for accommodating it and for making the school’s graded exercises and relevant learning experiences tolerable.”8 It would extend beyond the scope of this work to discuss all the reasons for the emergence of this wrongheaded approach to a humanizing education, but the results speak for themselves. They have been nothing but catastrophic: significant decline in academic competency, exorbitant abuse of student accommodations, massive grade inflation, and out-of-control violence. So much for “the romantic school of child psychology.”9

In Classical Christian Education, the teacher is not merely a casual transmitter of content but a model of the paideia life. That is to say, the teacher is not a teacher of curriculum, but a teacher of students. Neither is the teacher the student’s “buddy” or “friend.” Although Classical Educators ought to be kind and friendly, they also accentuate their status as an authority figure in loco parentis who inspires respect for their mastery of the body of knowledge they are teaching. Likewise, good Classical Christian Educators possess “the emotional commitment necessary for capturing the imagination of their students.”10

In sum, Classical Christian teachers shepherd students in the life of the mind, challenge them in the virtues of adversity by calling them to reach above what they think they are capable of, and guide them faithfully in the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. They do this not only through instruction and dialogue, but also by honest and candid assessment, and ultimately through inspirational imitation—living out what they teach, demonstrating humility in learning, and embodying the virtues they seek to cultivate in their students. Teaching, in this view, is not transactional; it is a deeply moral and spiritual vocation.

Paideia: A Legacy for a Life Well Lived

Recovering paideia is essential to recovering a meaningful and lasting vision of education. We are not preparing students merely to pass tests, get into college, or secure well-paying jobs. We are preparing them to live well. We are preparing them to become the kinds of people who can steward their gifts for the good of others and the glory of God.

In the chapters ahead, we will continue to build on this foundation, exploring how Classical Christian Education equips students with the tools of freedom, prepares them for college and life, immerses them in the Great Conversation, and orients them toward a life of virtue. But it all begins here—with paideia, the very soul of education.

Having learned a little better how to manage larger pieces of content, Chapter Two: The Seven Characteristics of a Classical Christian will be delivered serially by section.

This footnote will expand to discuss Nietzsche’s transvaluation of values and the subsequent development of logical positivism. It will further explain how atheism as a scholarly position was not possible until the Enlightenment and Christianity as a scholarly position only ceased being acknowledged in the early 20th century with the rise of secularism (see previous note on the difference between secularity and secularism).

Plato, The Republic: English Text, ed. T. E. Page et al., trans. Paul Shorey, vol. 2, The Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann Ltd., 1937–1942), 133–135.

Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics, Book II.

Augustine of Hippo, “The City of God,” in St. Augustin’s City of God and Christian Doctrine, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. Marcus Dods, vol. 2, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1887), 303.

This footnote will expand to discuss Dante’s project in The Divine Comedy (i.e., to lead the pilgrim out of the dark wood toward the Beatific Vision).

C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 24-25.

C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 26.

David Hicks, Norms and Nobility, 42.

David Hicks, Norms and Nobility, 37. This footnote will also expand to discuss this problem more fully by unpacking work done by Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge as well as the influence of Paulo Freire on American education. Abigail Shrier, Bad Therapy, 89-106; Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind; Carl Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, etc.

David Hicks, Norms and Nobility, 41.