Paideia: The Soul of Classical Christian Education (Pt. 1)

Chapter One: Untitled Primer on Classical Christian Education

As I mentioned in the first post in this series, I’m currently revising the second draft of a short seven-chapter primer on Classical Christian Education. I’m hoping to use this work to reach families who are unaware or less informed about the Classical Christian Education renaissance, so I thought I’d invite you into the process by sharing “the work in progress” publicly. Please feel free to share your feedback and help me title the book.

I had intended to drop each chapter, serially, but the second draft of Chapter One comes in at roughly 3,500 words—a bit longer than most folks will read on Substack. Instead, I plan to drop it in three post over the next few days. Here is the first installment.

CHAPTER ONE

Paideia: The Soul of Classical Christian Education

If we were forced to distill Classical Christian Education into a single word, I would argue for paideia. This Greek word, emerging from the classical period, is rich with meaning that far exceeds modern thinking about education. Paideia is not limited to what we today might think of as mere academic instruction. In the classical world, it encompassed moral training, civic responsibility, artistic expression, and the cultivation of virtue.

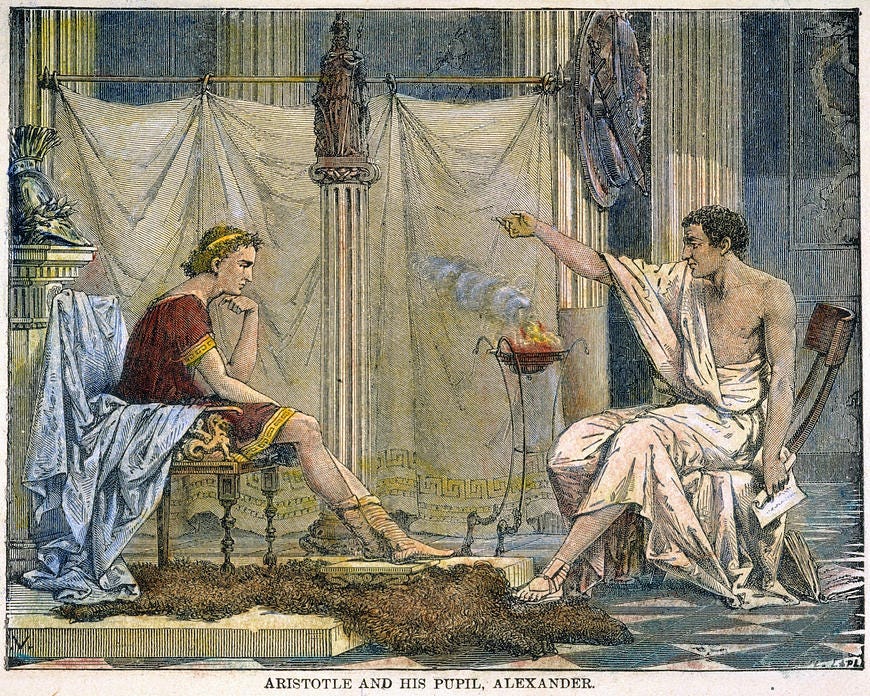

For the Greeks, paideia referred to the comprehensive and humanizing formation of a person, whereby the pupil was shaped into the ideals of Greek culture through imitation (mimesis).1 Mimetic learning meant paideia relied heavily on arts and letters, texts like Homer and Hesiod, and later Herodotus and Thucydides. In short, we might say paideia was the proper nurturing and formation of a human being toward the end of being a good citizen and living the good life.

The second-century Roman grammarian, Aulus Gellius (c. 125 – 180 AD), observed of Cicero that his idea of humanitas corresponded directly to the Greek idea of paideia because of its particular approach to education. Although some scholars believe Gellius’s perspective was somewhat over-simplified, in large part, humanitas was an attempt on the Romans part to capture and emulate the humanizing influence of the Greek spirit which sought to “help man discover his true self and therefore shape his personality” by putting before the pupil “with overwhelming clarity that ideal pattern of humanity which stirs our admiration [and]…the instinct of imitation.”2

The idea of paideia was not exclusive to the virtuous Pagans, however. Because of its universal and ubiquitous usage in the hellenistic period, early Christians adopted the term very naturally, much like they adopted theologias for theology (right speech about God) and ekklesia for church (the assembly of the body of Christ). Numerous Christian manuscripts from this period use various forms of paideia tou kyriou (i.e., the nurture/training/discipline of the Lord). There are even six instances of paideia in the New Testament (Ephesians 6:4; 2 Timothy 3:16; Hebrews 12:5,7,8,11).

When St. Paul wrote to the Ephesian Christians, he exhorted “Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline (paideia) and instruction (nouthesia) of the Lord” (Ephesians 6:4). St. Paul baptized this classical concept and infused it with Christian purpose. No longer would the ideal be to simply form good citizens of the polis; it would be to disciple faithful citizens of the Kingdom of God. The goal was not only virtue in the classical sense but also holiness and godliness. In a word, Christlikeness.3

Classical Christian Education, rightly understood, is the recovery and pursuit of paideia—the formation of the whole person in the truth, goodness, and beauty of God’s created order. In this chapter, we are going to explore seven key aspects of paideia and how it animates the very soul of Classical Christian Education.

1.1 Paideia as Soul Formation

Modern educational philosophies, at their best, tend to view students as disembodied intellects to be filled with information and trained with skills for the workforce—what some critical scholars have called “brains on sticks.” At their worst, they view students as mere material beings, evolved animals with therapeutic tendencies who have no further purpose for existing than creating their own satisfaction, avoiding suffering and death as long as possible, and functioning efficiently as consumers and cogs in the world system as long as they live.

Classical Christian Education is antithetical to both tendencies of modern education. It begins with the Christian belief that students are embodied souls.4 They are not mere mortals; they are eternal beings made in the image of God (imago dei) with hearts and minds, affections and imaginations, all of which must be properly nurtured and rightly ordered. The purpose of education, then, is not solely to inform but to transform.

This is the also the essential aim of Christ’s “new humanity” as St. Paul makes clear when he exhorts believers in Rome: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.”5 We are not simply transmitting facts; we are cultivating students to discern the good, acceptable, and perfect will of God—to be wise.

1.2 Enculturation in the Kingdom of God

All education is enculturation. And, “anyone who says differently is selling something.”6 Every school, every curriculum, every pedagogy—whether it acknowledges it or not—is passing on a particular worldview, a vision of what is true, what is good, and what is beautiful. That vision may be materialistic and secular, it may be Marxist and postmodern, or it may be Christian—or one of the other world religions. But it will never be neutral. Education is inherently presuppositional—like standing. A person can shift his weight to his left leg, to his right leg, or distribute his weight evenly between them. What he cannot do is stand on no legs. The weight of Classical Christian Education stands on historic Christian paideia and makes no pretense about its goal of enculturation.

Classical Christian Education intentionally seeks to enculturate students into the biblical narrative of God’s created order and the best that has been thought and said within the Western tradition. Through Scripture, history, literature, math, science, and the arts, students come to see themselves as participants in the comedic story of cosmic redemption, as language citizens of the West, and as contributors to the common good of mankind. They learn that although education is an ultimate possession, it is not for individualistic self-advancement but for faithful service in the Kingdom of Christ.

Tomorrow’s post will address:

1.3 The Wardrobe of the Moral Imagination

1.4 Piety as the Beginning of Wisdom

1.5 Community as the Context for Formation

This footnote will expand with cited sources to briefly explain mimesis, education through imitation, usually of character impressions (i.e. virtues and vices) through texts.

This footnote will expand with cited sources to briefly discuss the idea of Roman humanitas and its relationship to paideia. Werner Jaeger, Humanism and Theology, 21, and Eric Adler, The Battle of the Classics, 40.

This footnote will expand with cited sources to discuss David Hicks idea of the tyrannizing image and how God, through the Incarnation, provided Christ as that image—fullness of the stature of Christ. St. Paul asserts discipleship in the church (the community of the “new humanity”) works toward our full maturity: 13 until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ, 14 so that we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro by the waves and carried about by every wind of doctrine, by human cunning, by craftiness in deceitful schemes. *the word “manhood” in verse 13 is anēr and refers to full-grown manhood and is often translated husband.

This footnote will expand with cited sources to discuss the holistic view that historic Christianity as expressed in all creeds and catechisms affirm (i.e., WCF and Heidelberg catechism). The soul is the substantial form of the body, not an entirely separate entity temporarily lodged within it.

Romans 12:2, ESV.

If you know you know. (A memorable line Wesley, of Goldman’s The Princess Bride, gave to Princess Buttercup in regards to “life being pain.”)