Read The Prologue.

Midway along our journey from Las Vegas to Reno, my family and I wandered off the highway into a savage and stubborn wilderness to find a rest stop to let the kids take care of business. What we discovered though was a strange piece of history that compelled us to explore and photograph an old historic mining town.

Goldfield is situated in the middle of the Nevada desert recollecting shattered Ozymandias’ half-sunk, sneering visage. With nothing but vultures and sagebrush littering the lonely sands that stretch far from the doleful town in every direction, one half-expects to be greeted by a sign warning visitors: ABANDON EVERY HOPE, ALL YOU WHO ENTER. Dusty and dilapidated, the grim ghost town was replete with rolling tumbleweeds, run-down saloons, and boarded-up bordellos. It was the kind of place where it would have been a sin not to explore the graveyard, so we set out in search of the eerie necropolis and soon located a small grove of white headstones, where we parked the truck and stepped out into the windy inferno.

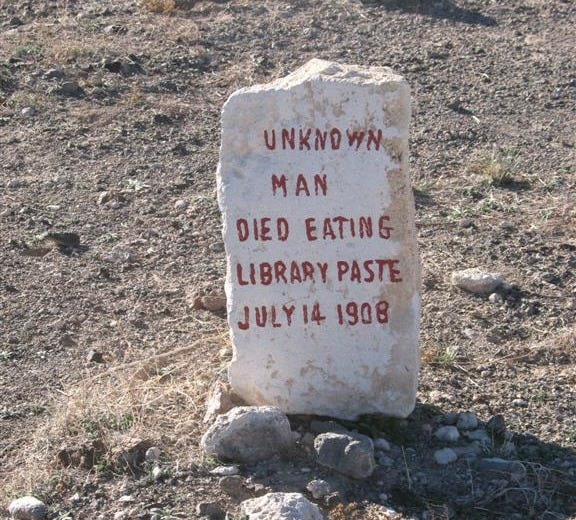

Wandering among the dated memorials trying to decipher the stories of shades who walked the dusty streets a hundred years before, we came across the most unusual and intriguing tombstone. In one sense, it was very much like the others around it. It was made of white stone, stood about 2 feet out of the ground, and was etched with letters that were highlighted with faded red paint. Unlike the others, however, this one didn’t have a name etched into it. Instead, it was inscribed with a surprising expression: “UNKNOWN MAN DIED EATING LIBRARY PASTE JULY 14 1908.”1

I’m reminded in times like these, that truth is indeed stranger than fiction. Like the front waters in an arroyo after a sudden desert rain storm, the questions came slowly at first, but soon swiftly, until they gained momentum and swelled into a flash flood of inquiry. Why was a grown man eating library paste? Was he starving? Is that all he could find to eat? Was he mentally ill? Did he know it was library paste? Was it a frivolous prank that rewarded him with death, or a dare that earned him the first Darwin Award? What was he thinking?

Soon, the more serious questions—the human questions—spilled over the trivial ones, distilling truth like the clear waters of Lake Tahoe. Who was this unknown man? Was he a prospector, a cowboy, or an outlaw? Where was he from? Were his parents living and looking for him at the time of his misfortune? Did he have children? Did he have siblings? Had he ever been married? Did those people who loved him ever know what happened to him? What was the nature of his spiritual condition? All of these latter questions were queries of identity. They were questions about his humanity. Whoever the unfortunate man was, his life ended, tragically, in a dirty mining town in the middle of a sweltering Nevada desert—and no one even knew what name to put on his tombstone. That thought startled me for two reasons.

The Significance of One’s Name

The first reason was because he was nameless. Throughout ancient history, a person’s name was symbolic for his or her identity, e.g. the name of the King of Israel and probable writer of Ecclesiastes, Solomon, means peace. Remarkably, his reign was a reign of peace. Later, through history the surname was often associated with the family trade or with the father’s name (i.e. Smith is derived from blacksmith, and if Solomon had a last name, it would have probably been Davidson). My name, Scott, was given to me for the relational significance it held for my parents, as it was derived from their favorite song, “Watching Scotty Grow,” by Bobby Goldsboro.

On another level, a name can stand for one’s reputation. It is common for people to say that an individual made a “name” for himself, meaning he succeeded in attaining some level of influence or renown. The Proverbs tell us, “A good name is to be chosen rather than great riches, and favor is better than silver or gold” (Proverbs 22:1, ESV). While, no doubt, one’s identity or character is not based on the semiotics of one’s name alone, and as such can potentially devolve into various forms of hubris and vanity, the idea that our name is significant to our identity is not without its merit. Like Abel of Genesis, the fact that this man died without a name, so to speak, though he was dead “yet speaketh” (Hebrews 11:4).

The Significance of One’s Story

The second reason it startled me was that he was dead. But it was not the dying part that frightened me; it was the living part. We will all die one day. As one fellow said, “No one gets off this planet alive.” And for the most part we have as much control over our death as we did our birth. In many ways, dying is the easy part to reckon with. The nameless dead man in Goldfield recollected another necropolis experience from years earlier, this time with a mob of teenagers in the middle of the night. For a youth activity, we did a scavenger hunt in a graveyard. The object was to decipher people’s stories just from the information written on their headstones.

Buried in a remote and overgrown plat of sacred land, we found stories of people who lived through the Great Depression, some who were more than a hundred years old when they died, and others who lived mere days on the earth. Like a three-act play, the headstones displayed the date of the person's birth, the date of their death, and a dash etched between them. These headstones reminded us life has a definite beginning, a definite ending, and some time in between. As Linda Ellis' poem suggests, "...what matter[s] most of all was the dash between those years." The dash is the only thing any of us have any significant control over, and that is what bothered me most about the unknown man’s tombstone. Not only was there no name, there was no dash.

This strange experience which started out as a short family pit stop on a long monotonous road trip, has for at least these two reasons, become to me, symbolic for understanding what significance looks like. To put it simply, to have a dash means to have lived, and to have a name worth remembering means to have lived virtuously. What I took away from this man’s tombstone, is that when I am dead, I want it to be said of me that I had lived a significant life.

The Significance of One’s Dash

Everyone gets a dash to do with as they please. We should consider it a gift from God with an expiration date. Those cemetery experiences teach us each day, each hour, each minute, and each second passes sequentially moving us closer to that expiration date—and there is nothing we can do to stop it. There is a premium on life. It has a limited supply, and our dash is the most valuable asset we have. We can't afford to waste it.

Here is another thing. Our dash is unique from all others. Ours is a life filled with experiences and opportunities different from everyone else's. All of the good experiences, and the bad, work together to shape us into the people we are. Our dash is like owning The Mona Lisa. There's only one and that makes it priceless. Within our dash we have a purpose to fulfill—a destiny as it were—that no one else can accomplish. Living a significant life is more than avoiding a tragic death in a remote desert mining town where no one knows who we are. It’s discovering what we were made to do and why. Ours is a life that if not lived significantly will leave a void in the world and emptiness in our soul.

And that brings me to the purpose for writing this book. Have you discovered the significance of your unique life? Do you know what your dash is for? If your epitaph was written today, would it tell a story of significance, or something else? In these next few pages, I hope to inspire you to discover your significance before the story of your dash is permanently etched on a tombstone in some obscure plat of sacred ground.

A Disclaimer

Before we turn the page, let me offer a brief warning, a helpful insight if you will, about three pernicious pitfalls in our own age that we will want to avoid on our journey to discovering our significance and stewarding our dash.

The first pitfall is the trap of complacency and sloth—often seen in prolonged adolescence. A lot of young people have fallen in this ditch because it’s now normative within the current cultural milieu to postpone, even evade, responsibility and maturity. By now it’s cliché—kids living in mom’s basement playing video games and watching porn or TikTok until they’re 30 yeas old, instead of pursuing a purpose: a job, a degree, a spouse, etc.

But its inverse can be equally or sometimes an even more dangerous pitfall because it’s so insidious. I’m talking about turning one’s life into a mad dash, always stressed, always busy, always racing against the clock, hurrying scurrying, fretting, and worrying. As I’ve discussed previously, some elements of our capitalist society (once undergirded by a healthy protestant work ethic), tend to idolize work as a thing which can or should be done for it’s own sake. Thus, “always stressed and busy” is a vice disguised as virtue.

A final pitfall has to do with what we mean by significant. I’ll address this more later in the book but to prevent the reader from being distracted by what might seem by some to be a philosophical misstep, significance does not mean worldly fame or financial renown as our culture often speaks of it. Vainglorious existentialism is not the meaning or the goal of living a life of significance.

Read Chapter Two: A Brush With Geometry.

I later learned the man was a vagrant who was in extremely poor health and was likely starving, according to the county physician, Dr. Turner, who examined the body. The man apparently “found a jar of book paste in the trash near the library. In addition to water and flour, [the paste] was made of 60% alum. The alum, along with his weakened condition, poisoned him, and he was found deceased near the automobile garage. Despite a letter addressed to the name ‘Ross’ found on him, the unknown man could not be identified.” The story was reported in the Reno Evening Gazette on Mon, Jul 20, 1908 (Page 8).