A Footnote, A Star, and the Little Orphan That Could

Chapter Three of Discover Your Significance

A Footnote in Someone Else’s Story

We all know Bruce Wayne, the billionaire industrialist behind the bat mask. But do you know Ron Wayne (no relation to Bruce of course)? To understand who Ron is, we have to start with a couple of names you probably do know, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. They were the masterminds who developed Apple, Inc. from a garage-based personal computer company into a multinational corporation with cash reserves at one time larger than that of the federal government.

By the time Steve Jobs succumbed to his battle with cancer in October of 2011, his was a house-hold name. And Steve Wozniak’s was nearly as conspicuous. The name most people don’t know, however, is the third co-founder of Apple—Ron Wayne.

In 1976, Ronald G. Wayne lost his senior development job at Atari due to a Warner Communications acquisition. Soon after, he authored the first contract between himself and the two Steves. Twenty years their senior, he was a promising entrepreneur with a lot of experience in start-ups and a fair amount of wisdom to bring to the table. But as soon as Jobs started borrowing money to get their concept out of the garage and into homes, Wayne got cold feet and wanted out.

Having previously lost a significant investment in another risky venture, and believing time was not on his side (he was 41), Wayne left Apple after just a few months, selling back his 10% share of Apple to his partners for $800. (Sometime later, as Apple began to take off, Wayne was paid an additional $1500 as surety against further interest in the company.) Today, Wayne’s stake in Apple would be worth something in the neighborhood of $22 Billion. At the time of this writing, the 90-year-old Wayne still lives in a mobile home park in an obscure desert community an hour outside of Las Vegas, NV. He ekes out a living by selling coins and stamps to supplement his Social Security checks. For $2300.00, Ron Wayne bought his security and stayed safe in the bottom tier of the pyramid.

Of course, everyone is entitled to his or her own personal pursuits, and there is nothing inherently wrong with living in a mobile home. My point is not to shame Wayne for his decision, or judge the man for how he stewards his life and his assets given he believes he made the best decisions he could with the information he had. As a matter of fact, Wayne made it clear to journalists that even though Apple was, at one time, the most valuable company in the world, given the risks and stress he knew he would have to endure if he stayed with Apple, he "probably would have wound up the richest man in the cemetery.”

Nevertheless, his story epitomizes man’s temptation to pursue security even though the alternative might mean taking a calculated risk to secure more opportunities and a decent level of satisfaction. Unlike Jobs and Woz, who stretched themselves to pursue what they genuinely loved, Wayne played his cards close to the vest and protected his $800.00 investment from disaster.

In another interview, Wayne, then 76, asked the journalist if his life was really so interesting that it would be worth traveling to the remote desert and spending a couple of days asking him questions. When the journalist indicated it was his time with Apple that made it so intriguing, Wayne replied, "Oh, so it's my brushes with famous people. I'm a footnote in someone else's story." Unfortunately, Wayne was right. We can climb out of the secure zone and do something that satisfies—better yet, we could discover our significance—or, we can play it safe and be a footnote in someone else's story.

A Star that Failed to Shine

When Steve Jobs died in October of 2011, the whole world paid attention. It was front page news. It even seemed a little ironic to receive the breaking news of his death on my iPhone. The reason Steve Jobs' death was so personal to the world was because he created a satisfying product for them. He literally changed the technological landscape with his ingenuity.

In a commencement address at Stanford in 2008, he encouraged students to pursue a liberal arts education, explaining to the graduates that learning calligraphy at Reed College was what opened the door for the way personal computers would display information. He invented a way to turn calligraphy into something he called fonts. Maybe you've heard of them.

But Jobs’ tech inventions are only part of his story. To get the fuller picture, we need to start at the beginning of his life. Many may not realize Steve Jobs started live as an orphan—sort of. In fact, he was given up for adoption by his graduate-school mother while she was still pregnant with him. Then, at his initial adoption, he was ultimately rejected by the parents who had already agreed to take him. They decided last minute they actually wanted a girl. Steve was, for all practical purposes, rejected twice before he was ever born.

The adoption that would eventually yield him parents nearly fell through as well. This time it was at his biological mother's behest. At the eleventh hour, she refused to sign the adoption paperwork when she discovered Steve’s soon-to-be-adoptive mother was not a college graduate. Eventually, she relented and agreed to let the Jobs family adopt him with a stipulation—Steve would have to go to college.

Jobs did go to college. For a while. He dropped out of college early to save his parents' money. He told his friends and family he felt bad they were spending their life savings to put him through school. After moving home to California, he started a little home-based computer company out of his parent's garage with a friend. He called it Apple. Ten years later it was a highly-successful, $2 billion company. Things were looking really good for Jobs—until the board of directors fired him.

He was devastated. He didn't want to stay around to watch the company he started succeed without him. So, he made plans to leave the Silicon Valley and start over somewhere more private. But before he pulled the trigger on his move, he realized he would be leaving what he really loved. He decided to begin again where he was. This time he started a company called NEXT. NEXT was not nearly as successful as Apple, but Jobs eventually acquired Pixar and things took another drastic turn—this time for the better. Soon Apple offered to acquire his companies and hire him back as CEO. And as the cliché says, the rest is history. Jobs took the reins and Apple became one of the most important and influential companies in the world.

Ronald Wayne played it safe and walked away with $2300.00. Steve Jobs impacted the world because he took risks and pursued his passion. It’s plausible to think Jobs discovered his significance at Apple. But, it would be more accurate to say he discovered his satisfaction in the tech industry.

Unfortunately, as genius and passionate as he was, only God could have saved Jobs from premature death. In 2011, at just 56 years old, Jobs succumbed to the cancer he had been battling for some years. There is no question Jobs rose above the consuming need for security most humans struggle with, and he did some truly amazing things in this life. Yet, in reality, he was able to take none of his success with him when he died. As Horace laments, Pallida Mors aequo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas regumque turris.1 The Psalmist assures us of this when he writes, “For when he dies he will carry nothing away; his glory will not go down after him” (Psalm 49:17).

Death is the great equalizer. It comes for all of us, putting an end to our works, whether they be great or small. Inevitably, there will come a time in history when the iPhone will go the way of the rotary phone; it will be a footnote in the history of the tech and communications industries. This then begs the question, if the satisfaction of building something great for the world is inexorably doomed by death, what does it look like to truly discover one's significance?

To answer this question, we’re going to turn the clock back 2,500 years and investigate the life of a third underdog—another orphan who unexpectedly discovered her significance. And to heighten the suspension, hers was not a serendipitous discovery.

The Little Orphan that Could

Steve Jobs' story is fascinating, for sure. There is something satisfying about the underdog turning failure on its head and making a success of his life despite the odds. But there are stories greater than his—ones where the underdog-turned-hero saves the day—like a modern superhero, but for real. History is so replete with such “fine examples to take as models” that it would make Livy giddy with delight.2

You probably don’t know it yet, but I suspect when you discover your significance, that story will be yours too. But before we get to that part, let me introduce you to the orphan who discovered her significance. She was not an entrepreneur like Wayne, or a tech genius like Jobs. Rather, she was a young immigrant in a foreign country without any rights to speak of. Yet she saved an entire race of people from genocide.

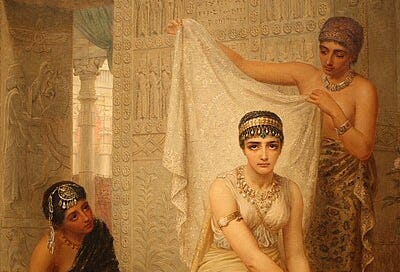

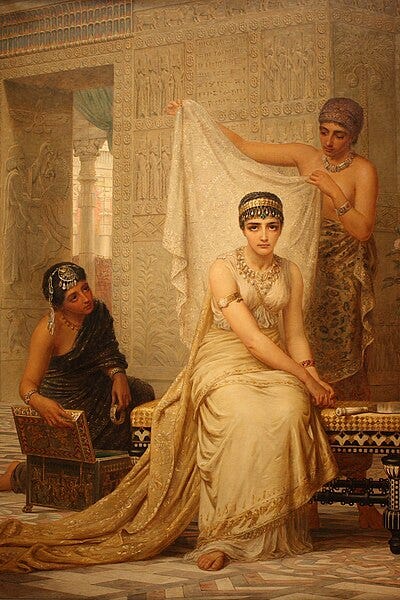

Hadassah’s story takes place between 486-465 B.C. in Persia, in the vicinity of the modern country of Iraq. Xerxes (pronounced Zurk-seez) is the ruler of Persia. In the third year of his reign, he hosts a feasts for his palace dignitaries, soldiers, and servants. During the final week of the celebration, Xerxes gets stupid drunk and sends for his wife so he can "show her off" to his dinner guests. As you might expect, his debauched plan doesn’t go over so well. Vashti declines his summons outright. Drunk, embarrassed, and angry, Xerxes divorces her on the spot.

About three years later, during the sixth and seventh year of his reign, Xerxes attempts to finish his father’s assault on the Greeks, after Darius suffered a massive defeat at the battle of Marathon (490 A. D.). Xerxes decimates the Spartans at Thermopylae, but is soundly defeated a short time later at Salamis. Returning home from his humbling defeat he seeks consolation and distraction from his great disappointment. One oversight, though. He deposed his wife years ago. And according to Persian laws and customs, he is a god, so his decrees can never be reversed (It seems drunken gods don't make great decisions).

So with the help of his counselors, Xerxes remedies his situation by hosting a six-month feast in his palace at Susa. He also organizes a beauty contest to find a new wife who will replace Vashti as queen. (Xerxes likely had multiple wives and mistresses, but it seems likely only one maintained the royal status.) Indeed, Xerxes finds a maiden he likes, a Jewish orphan named Hadassah being raised by her older cousin, Mordecai. In a sudden move of Providence, the ragamuffin is raised to royalty.

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end on that high note. It’s actually only the beginning.

Hadassah’s cousin Mordecai is a scribe in the king's court. But he has a problem. One of the court officials, an antisemite in the king's inner circle named Haman, is daily becoming more antagonistic toward Mordecai (and toward the Jews as a whole). Finally, Haman’s pot boils over when Mordecai refuses to bow to him, and he cunningly secures the king's permission to set a date for a Jewish hunting season. It is the most elaborate ethnic cleansing scheme dreamed up by any devil.

But if that is not bad enough, the plot thickens again when Xerxes unwittingly humiliates Haman in an attempt to honor Mordecai. As Providence would have it, at an earlier time, Mordecai uncovered a plot to assassinate Xerxes. Xerxes, unable to sleep one night was reading through the kingdom’s chronicles and realized he never rewarded Mordecai for exposing the traitors. In return for his faithfulness and bravery, Xerxes has Haman lead Mordecai through the streets of the Capital on the king's horse wearing the king's robe. All the people, including Haman, are required to bow to Mordecai and show him the honor of a king. This is too much for Haman. To end his torment, he constructs a private gallows at his estate where he can have Mordecai hanged.

Just then, Mordecai is horrified to discover Haman's plans to exterminate the Jews throughout the kingdom. Distraught, and in good Hebrew fashion, Mordecai pours ashes on his head, tears his clothes, and sits in the middle of the street near the palace crying to God like Rachel weeping for her children, refusing to be comforted. His antics quickly gain the attention of the queen's butler, who relays the scene to Hadassah. Deeply saddened and probably a bit embarrassed, she sends a messenger to Mordecai to compel her cousin to leave the streets. But, instead of conceding, he begs Hadassah to go to Xerxes and plead for their lives. All the queen has to do is tell the king of Haman's treacherous plan to exterminate the Jews and ask him to put a stop to Haman's madness. Then they can all live happily ever after.

Hadassah refuses. She declines out of fear. She would be risking her life. Another bizarre law in the Persian culture states that no one—not even the queen—can approach the king without his request. And, Hadassah has not seen her husband in more than a month. He has not even bidden her for connubial favors. If she approaches the throne without his request, she will be executed—unless, by an extreme act of mercy, like a presidential pardon, the king extends his scepter to her as a sign of forgiveness.

But, remember Vashti? Xerxes is not a forgiving man. He is a battle-hardened, narcissistic emperor who believes he is a god. The stakes are high. The tension is thick. An entire race of people within the kingdom is going to be annihilated in a matter of weeks. Mordecai is so burdened by the pending destruction, he appeals to Hadassah a final time.

In desperation, he cries to her:

Do not think to yourself that in the king's palace you will escape any more than all the other Jews. For if you keep silent at this time, relief and deliverance will rise for the Jews from another place, but you and your father's house will perish. And who knows whether you have not come to the kingdom for such a time as this?

Mordecai confronts Hadassah with two important warnings. First, she's not going to escape execution just because she's the queen. Second, maybe—just maybe—it was Providence that made her queen after all. Perhaps this is the reason for which she was created. Maybe this is her destiny—her unique and significant role to play in the world.

Read Chapter Four: The Rest of the Story

Translated, Pale death knocks with impartial foot, at the door of the poor man’s cottage, and at the prince’s gate (Book I, Ode IV).

The Roman historian, Titus Livy, famously stated, “The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see; and in that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.” Titus Livy et al., The Early History of Rome: Books I-V of the History of Rome from Its Foundations (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 30.