Ἀγεωμέτρητος μηδεὶς εἰσίτω. - Plato

Read Chapter One: Lessons From a Tombstone.

Introduction

Since we were just on the subject of tombstones, you might find it interesting to know that the iconic shape that has come to characterize the lithoscapes of many cemeteries, especially during the Victorian-age—that upright rectangular slab with a rounded or semicircular top—is geometrically known as a Norman arch.

It is derived from the Norman window, a Gothic architectural design based on Romanesque arches commonly found in Cathedrals built during the Medieval period. During the Neoclassical and Gothic Revival of the late 18th and 19th centuries, funerary art adopted, among other Romanesque and Gothic symbols, this practical and spiritually significant design for their tombstones. As it so happened, this aesthetic revival simultaneously occurred during the heyday of the Industrial Revolution when the standardization of production methods were of chief concern to manufacturers. Because the Norman arch was aesthetically pleasing to society and also fairly straightforward to carve, it made production simple and economical. It soon emerged as the practical, dignified, and symbolically rich choice for Victorian culture.

The Norman arch is composed of two geometrical figures seamlessly integrated, a rectangle and a semicircle whose diameter matches the width of the rectangle that it sits on. Historically, whereas the rectangle or “quadrangle” was said to represent the earth, the circle is said to represent eternity and completeness. As a geometric symbol, the Norman arch presented an aesthetically pleasing symbol that spoke to the unity that exists between the earthly and heavenly realms. It is, in a word, anagogical, a reminder to every onlooker that human beings have eternal significance, that our destiny is eternal. C. S. Lewis captures this same vision of human significance quite well in his book, The Weight of Glory. He writes,

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal.1

The geometrical shape of the Norman tombstone is significant because it is meant to remind us that under that sacred plat of ground, for which the stone serves as a marker, lies an immortal person, a creature who in his eternal state you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else find a horror and a corruption such as you now meet only in a nightmare. Some people will have the fortune of having a brush with death that will open their eyes to such an anagogical vision, where they are able to truly behold the significance of their life. There is a sense in which such a brush with death is a gift. But anyone who’s ever been to a graveyard or cemetery has been fortunate enough to have their own brush with geometry.

Geometrical Significance

It’s no wonder why such a symbol comprises so much significance. Beginning with the 6th Century B.C. Pythagoreans and extending all the way into the Early Modern period, geometric figures and their related theorems have consistently held spiritual and philosophical significance for understanding the cosmos and the human condition. This is why Plato famously inscribed over the door of his academy the words of the epigraph that opens this chapter (translated, "Let no one untrained in geometry enter.”). Fundamentally, Geometry is the study of number in relationship to space. At its core is the study of form and structure by way of complex reasoning. The ancient philosophers like Plato, recognizing its significant contribution to human thought, made its mastery a precursor to studying philosophy.

By the early Medieval period it continued its crucial role in education as one of the seven Liberal Arts. These humane arts consisted of the Trivium and the Quadrivium. Within the Trivium (Latin for three ways) subsisted grammar, logic, and rhetoric. The Quadrivium (Latin for four ways) was made up of mathematics (the study of number), geometry (the study of number in space), music or harmony (the study of number in time), and astronomy (the study of number in space and time). Geometry has remained essential because it has the capacity to reveal truth about the cosmos and our relationship to it by its reliance on clear principles and unchanging truths—axioms and theorems which reveal objective structures within reality. The enduring attraction to Geometry is not only found in its ability to cultivate mental discipline and an appreciation of harmony—qualities that are themselves essential to human flourishing—metaphorically, it illustrates our human desire to understand our existence, find stability amidst flux, and navigate the tension between chaos and order.

The Triangle and Abraham Maslow

One of the chief and most enduring geometrical structures to shape moral and philosophical understanding in the Western tradition has been the triangle. For example, whereas in the classical world, the Pythagoreans claimed “all is number,” Plato asserted “all is triangle.” In his dialogue, Timaeus, he asserts that the physical world, in its most basic components, is fundamentally geometric—elemental forms shaped from simple, ideal triangles. For Plato, this was more than an explanation of the material world. It had theological and philosophical implications. He believed the cosmos, including the material world, was rationally and harmoniously created by a Divine Craftsman (he called it The Demiurge) in such a way that physical reality ultimately reduces to intelligible forms that human reason can understand.

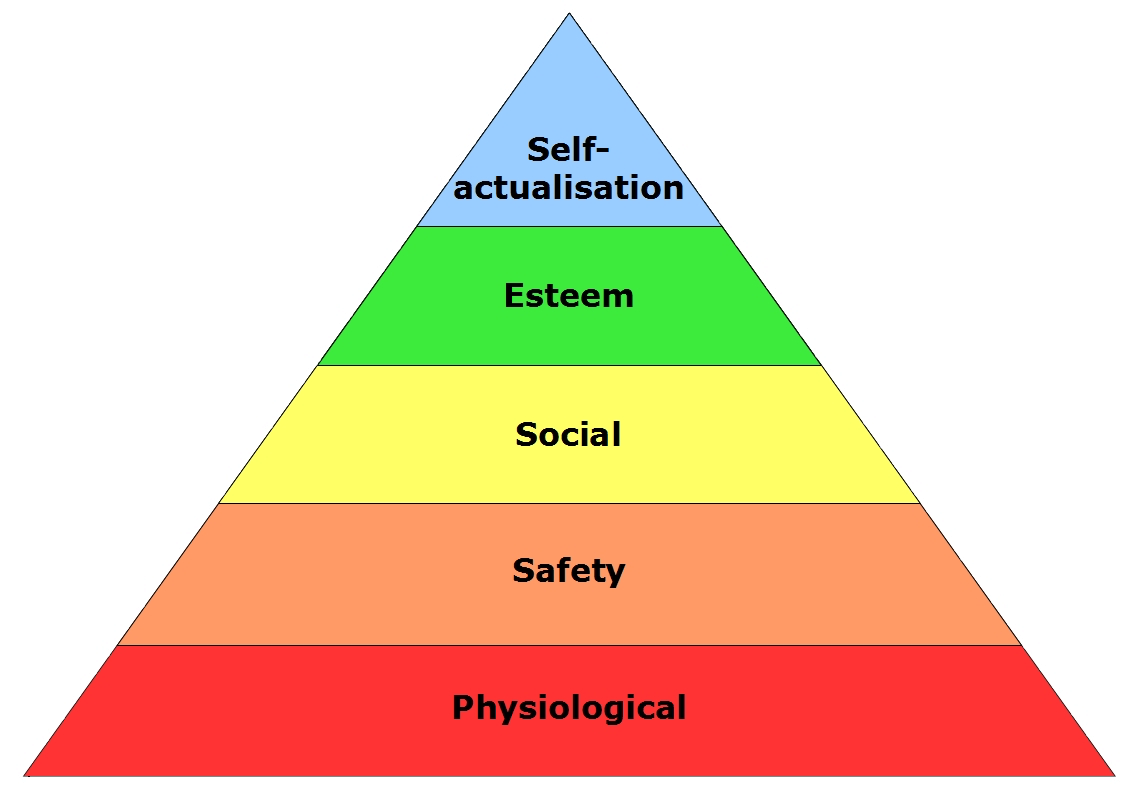

Jumping ahead in time to our modern age, it is not insignificant that the renowned psychologist and philosopher, Abraham Maslow, used a pyramid to illustrate his now-famous Motivation Theory, particularly his Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s research played a crucial role in shaping human thought for a period of time in the modern era because his approach was humanistic in its framework, meaning he emphasized a more holistic view of human nature than his predecessors, one that was consistent with historic humane traditions.

In opposition to Skinner’s Behavioralism, which was rooted in deterministic assumptions, and Freud’s Psychoanalysis, which was rooted in unconscious repressed drives, Maslow viewed human nature through the lens of motivation. He insisted that human beings naturally seek truth, beauty, meaning, and moral goodness. Obviously, the last of these imply Maslow was not a Christian who believed in original sin. In fact, he was an atheist who rejected organized religion on the grounds that much of Christianity’s religious dogma constrained rather than liberated human potential. Nevertheless, he did acknowledge the human need for transcendence and viewed religion, when used positively, as a means to higher self-actualization. In this regard, Maslow stands in line with many of the virtuous Pagan thinkers who affirmed human flourishing but were flawed in their understanding of the need for human redemption.

Because of his more holistic view of human flourishing which emphasizes individual dignity and the moral-spiritual dimension of human life, his views resonate strongly with classical and Christian humanist thought, reflecting, for instance, Augustine’s restless heart (Confessions) and Aquinas’s telos-oriented human nature (Summa Theologica). And, since all truth is genuinely God’s truth, we can cautiously draw copious amounts of wisdom from humanistic thinkers like Maslow.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

As I previously mentioned, Maslow expressed one aspect of his understanding of humanity in terms of motivations, and he modeled these in the form of a pyramid (an isosceles triangle) called The Hierarchy of Needs.

At the base (the widest portion of the pyramid) are humanity’s physiological motivations, our basic survival needs—food, water, shelter, clothing, reproduction, rest.

On the second, still broad but slightly more narrow level, is the human need for safety: security, employment, health, and other resources.

On the third, and even more narrow level, is Love and Belonging: family relationships, friendships, and sexual intimacy.

Moving up to a still increasingly more narrow level is Esteem: respect from others, competence, achievement, and recognition.

In his earliest model, the pinnacle of the pyramid is Self-actualization: realizing one’s full potential, creativity, authentic living, morality, spiritual growth.

In a later model he added three more levels. Between Esteem and Self-Actualization, he placed cognitive needs and aesthetic needs.

At the very top, he added Transcendence to cap Self-Actualization.

Many leadership, business, and self-help books have drawn from Maslow’s hierarchy to discuss various aspects of human flourishing within their respective contexts. For our purposes, we will simply summarize its meaning by sectioning off the various levels into just three tiers. The first, or bottom and broadest tier, represents mankind's need for security; the middle, more narrow tier represents mankind's need for satisfaction; and the top tier represents mankind's need for significance. Admittedly, this is an oversimplification, but again, it's adequate for our purposes here.

Security, Satisfaction, and Significance

Security

Starting on the bottom of our pyramid, we have the baseline of security, similar to Maslow’s model. More than anything else, humans need this. We all have essential needs, like food, water, and shelter. But we also have other important security needs and we are willing to pay a price for them. For example, we buy life insurance, health insurance, gym memberships, and home warranties. We secure client contracts, retirement accounts, and some go so far as to establish prenuptial agreements.

Unfortunately, our struggle for security is mostly in vain. We still get sick, still have recessions, still get divorces, and still die. I'm not being cynical or advocating negligence here, but it's safe to say, living merely for security is living for nothing at all. Life has little significance when it is lived out exclusively in the security tier. In order to discover our significance, we have to rise above our preoccupation with security.

Satisfaction

Rising above security, in the middle of the pyramid, we find some of our satisfaction. In Maslow's pyramid there are various kinds of “satisfactions.” Agains, we will keep it simple and lump them all together. The bottom line is, in addition to security, we all desire to be satisfied. We all want to be happy. We can be secure without being happy, but we cannot be truly happy unless we stretch ourselves beyond the tier of security and reach for satisfaction. Satisfaction can be risky, but it's mostly obtainable. But we have to leave our comfort zones—our safe zones if you will—to achieve it.

The problem, however, is satisfaction—as it is found in the middle of the pyramid—is usually only temporary at best. Once we achieve one kind of satisfaction, we start looking for another. It seems sustained satisfaction (or true happiness) is always just around the corner, but never entirely within reach. And if we do grasp it, it's gone before we realize it. Like a snow flake in the palm of our hand, it dissolves before we can fully appreciate and enjoy it. If we are going to discover our significance, we must reach beyond security, and beyond mere satisfaction.

Significance

At the pinnacle, the very highest and most narrow level, is where we discover our significance. It's something all of us desire; but remarkably, too few people actually attain it. That’s why it’s referenced at the narrowest point on the pyramid—the pinnacle. Maslow called this pinnacle self-actualization, having borrowed a term first coined by Kurt Goldstein. It means "What a man can be, he must be." It can be summarized as the pursuit and realization of one’s highest potential as a human being.

This apogee is where we become all we are made to be; it's where we realize and actuate our potential as a person. It’s insightful, however, that Maslow later capped his previous pinnacle (self-actualization) with a new pinnacle, transcendence. As we'll see shortly, the pinnacle of significance is a bit higher than mere self-actualization. Significance is where our passion, our calling, and our identity all converge for the greatest good and our ultimate satisfaction.

Conclusion

To recap, geometrical shapes have long served as powerful symbols in the human experience because to behold and study them requires sustain and reasoned contemplation that give way to divine insights about the cosmos and ourselves. For Maslow, the pyramid (isosceles triangle) was a way of expressing, in most profound terms, and our relationship to security, satisfaction, and eternal significance.

We can survive by just having our basic needs met. Yet, most of us yearn to trade out security for a bit of satisfaction if the reward is big enough and the risk small enough. But we thrive—we live the abundant life we were meant to live—only when we live in the tip of the pyramid, when we know that our lives are meaningful.

To experience real security and sustained satisfaction, we have to know our lives count for something significant. Significance is what life is made for. Don't misunderstand. I'm not talking about vainglory, being egotistical, or suggesting we strive for self-centered success. I'm talking about living a life that really counts for something bigger than the illusion of security and the temporality of satisfaction. To illustrate this point, I would like to introduce you to three interesting people in the chapters that follow.

Read Chapter Three: A Footnote, A Star, and the Little Orphan That Could

C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory: And Other Addresses (New York: HarperOne, 2001), 45–46.